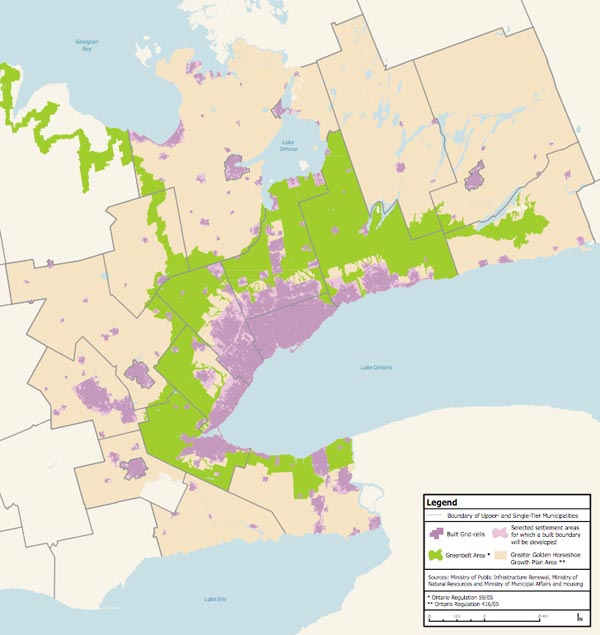

GTA population grows by 9.2% since 2001

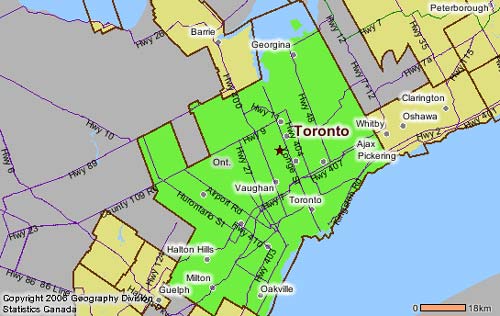

Statistics Canada has started to release data from the 2006 census at the City level – including population figures for Toronto and the GTA (or at least the Toronto Census Metropolitan Area (CMA), mapped above). By this measure, the GTA has grown 9.2% since 2001, with a population of 5,113,149 – that’s an increase in population of 430,252 in five years. The City of Toronto itself accounted for only 21,787 of this increase (with a very modest growth rate of 0.9%, and despite what most of us would think of as a significant high-density condo boom) which gives you an idea of the massive pressure on land development at the edges of the city.

To put that in perspective, the increase is equivalent to adding the entire Kitchener CMA (which includes Kitchener-Waterloo and Cambridge)(451,235), or the entire London (ON) CMA (457,720) to the GTA in the last five years. That’s very nearly the entire population of Newfoundland and Labrador (505,469), and eerily near the population of the City (not CMA) of Vancouver (578,041).

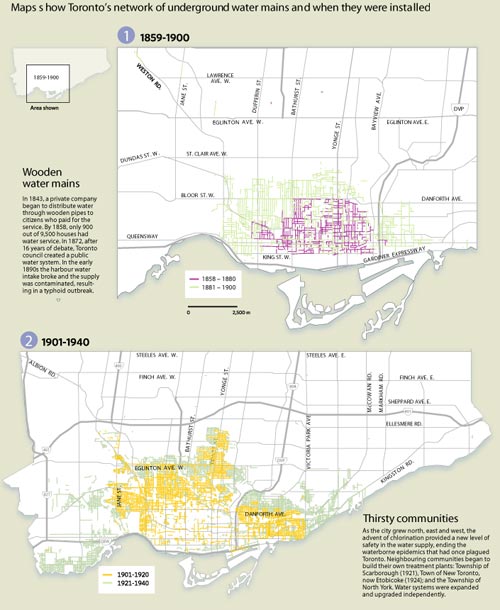

This only emphasizes the critical importance of GTA-wide planning along the lines of the Places to Grow work being done by the Province, but also makes one wonder where this type of planning was 10 or 20 years ago when we really needed it. If this kind of growth keeps up, the Provincial target to have 40% of new residential units inside the current urban boundaries is going to be a real challenge.