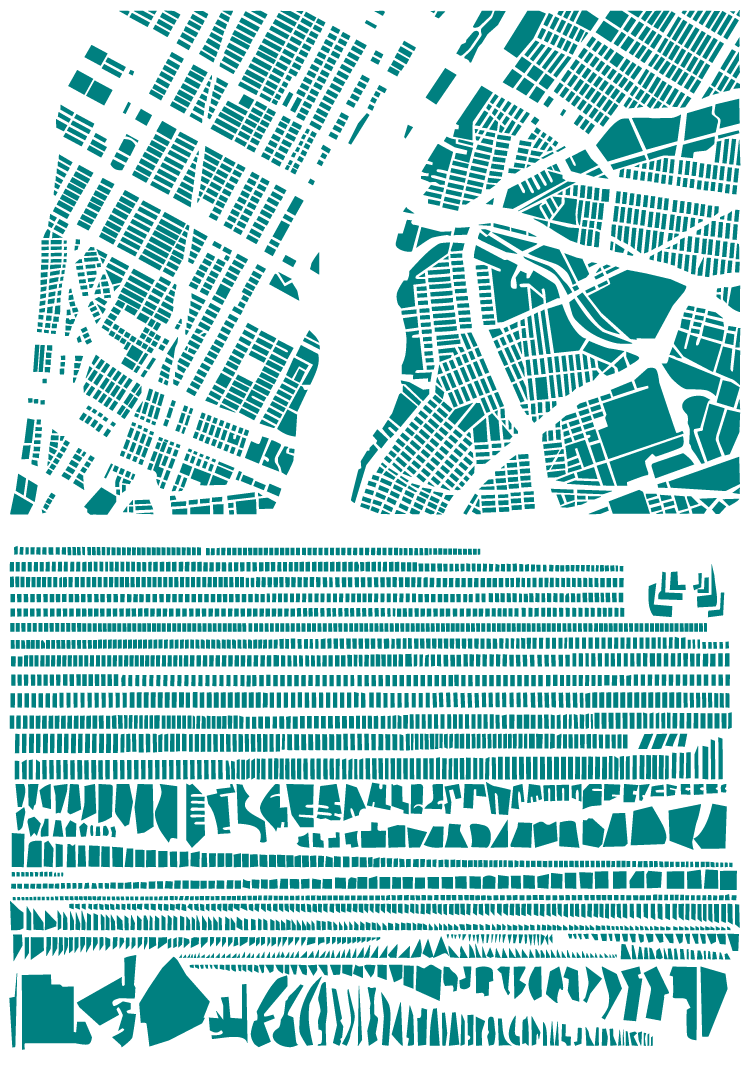

Photo: St. Thomas St, Yorkville

A second construction hoarding was erected on St. Thomas St south of Bloor recently, across the street from an existing hoarding (which has since been taken down). For a short time, the two facing hoardings protecting the sidewalks appeared to resemble a street lined with arcades, in its small spatial scale not unlike many you will see in southeast asia, such as this one in Singapore.

Photo: Street/lane in Singapore

This small scale of space is a relatively infrequent occurrence in Toronto, especially as part of a public street. While we’re used to such small scales in our back alleys, those alleys are, with but few exceptions, the city’s backdoors – infrequently travelled and largely empty, with few uses facing on to them other than the occasional residence and dominated by garages or blank walls and service entries. They do not really form a part of the public face of the city or city life.

Photo: Laneway in the Junction

Photo: Kensington Market (photo by raptortheangel)

Somewhere approaching this scale of space that is part of the public face of the city is most famously exemplified by Kensington Market, where not only the buildings, produce and products are jostled up against the sidewalk, but the streets are narrow and bustling with people, and to add to the compression of space, filled with parked cars and delivery trucks and slowly crawling traffic. It all adds up to a very human (dare we say humane?) scale that somehow makes you feel comfortable, as though you’ve been enveloped in the city. In fact, Kensington moves beyond a sense of space, and somehow transcends that rather empty word, to have evolved a sense of place, one that is both undeniable and unique.

Photo: Wilkins Ave, off King St E, east of Parliament

There are a few other examples of small space in the city, but they tend to be rather hidden and brief moments – although that just makes them seem all the more jewel-like when you discover them.

Photo: Tree-lined street at Rice University, Houston

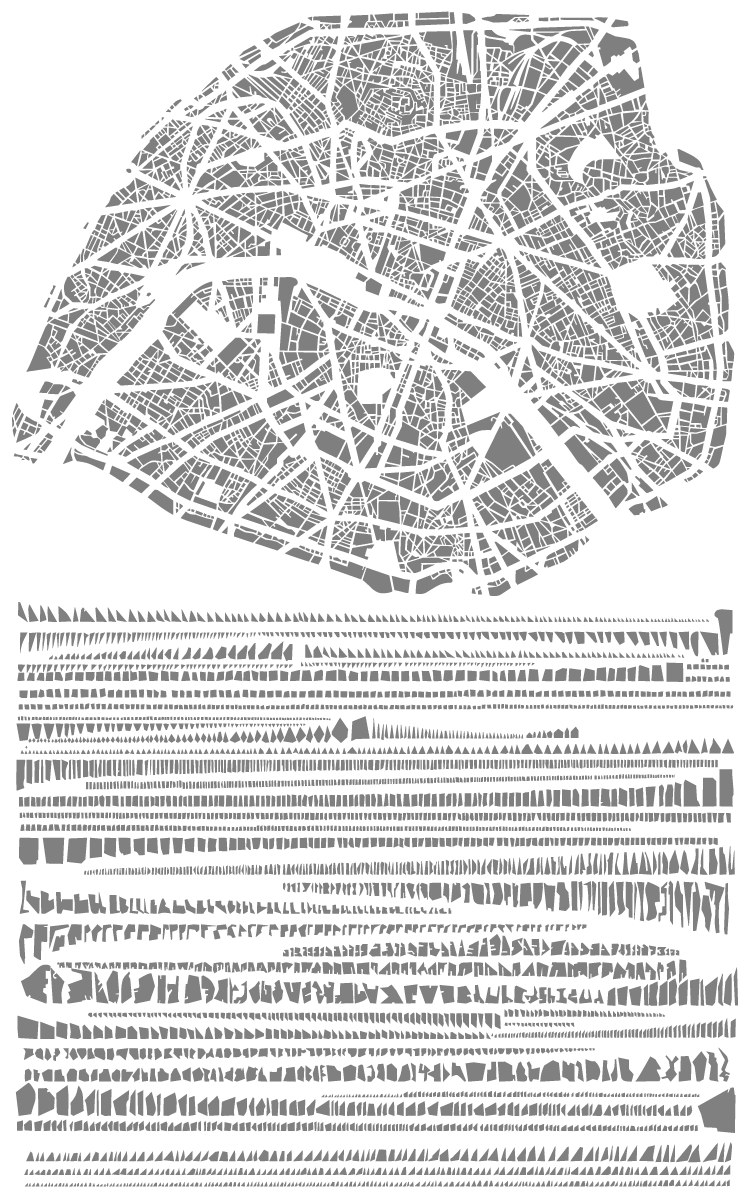

While small space is not the only way to attempt to foster sense of place, I think that there is some connection between this sense of scale, sense of space and sense of place. Similar effects of scale can even be created by the canopies of closely-spaced street trees, as at Rice University (above), but can also be misguided in implementation as in this accident of line-of-sight where Casa Loma’s tower is perfectly framed by the laneway between Walmer Rd and Spadina Rd south of Davenport, which doesn’t so much benefit the laneway itself, but creates some sense of drama and intrigue for all those people walking along MacPherson Ave towards George Brown College.

Photo: Looking towards Casa Loma up rear lane between Walmer Rd and Spadina Rd

Whether or not anyone agrees with me about the importance of small scale when it comes to sense of place, I think we can safely say that a key missing ingredient in the urbanities being created in suburban locales around Toronto (and the rest of north america) is the absence of small-scaled space. This absence has been compensated for in many different ways, but most notably (need I say, horrifically and ironically?) by the deliberately pedestrian scale of space of the “shopping street” inside the typical mall and, more recently, by the creation of “pedestrian-oriented” centres in suburban locales, usually surrounded by seas of parking and/or parking garages and huge arterial roads and/or expressways. These new “centres”, sometimes presumed to be the end of the mall (and often replacing them), are in reality the mall’s evolution into a more plausible (but still staged) “reality”, one that is once again based upon the smaller scale that has become nostalgically associated with our cities’ historic centres and main streets.

Whether this small scale can once again be more fully integrated into the urban environments we are building may depend on the level of commitment we as a society are willing to make to creating spaces and places planned and designed around people instead of cars. On this question the jury’s still out. Despite recent progress and a lot of talk to the contrary, the evidence on the ground does not convince.