An Urban School Drop-off Debacle

Huron Street Public School is a block and a half north of Bloor Street West, two short blocks east of Spadina Road, right in the Annex in downtown Toronto. It is within very easy walking distance of three subway stations – St. George, Spadina, and Dupont (roughly 250 m from the first two). It is also surrounded to the east by numerous 6-10 storey apartment buildings along St. George Street and of course sits within the famous, leafy, and relatively dense Annex neighbourhood, the same neighbourhood Jane Jacobs chose to live in when she moved to Toronto from Greenwich Village so long ago. She still lives just a few blocks away.

Given all of this, I am just dumbfounded at the number of people in this neighbourhood who seem to believe it necessary to drive their kids to school. The pictures above speak for themselves. There is no parking allowed on either side of Huron Street in front of the school. The teachers have their own car park around the side of the school. Every single car you see in the photos is there temporarily dropping someone off. It’s embarrassing, to put it mildly.

It’s also ridiculously dangerous. I cycle past the school every day – with cars stopped on both sides of the street, and two lanes of through traffic (mostly also parents) still moving between the stopped cars, it’s a cacophony of accidents waiting to happen as kids do their best to run from one side to the other amidst this mess. The worst insult is that the parking managment strategy of disallowing parking on this section of the street is a tacit approval for and enabler of parents to continue this negative behaviour.

The empty photo speaks volumes – the residential street is four lanes wide, a width that not only promotes parents in driving to drop their kids off (because there’s so much room to do so) but also seems to encourage speeding at off-peak times, while making it more difficult to cross the street. Is it not worrisome that even in the inner city, in Jane Jacobs’ own neighbourhood, we’re doing this bad of a job at promoting walking to school? How can we complain about suburban attitudes to driving, and especially school drop-offs, when this terrible example is sitting in our own backyard?

It looks like there’s a lot of work still to be done in changing even urbanites’ attitudes towards and use of the automobile. I can only hope that some enterprising activist public space organisation will get its ass out of Kensington one of these days and start “occupying” the drop-off space in front of Huron Street Public School and others like it. Now that I would like to see.

Of course, I’m also sure that building “a bicycle expressway along Bloor/Danforth” would solve this whole problem. Right? (that’s sarcasm in case you can’t tell)

Bicycle Lane Futures

This is Harbord and Montrose in the west end of Toronto. It’s a marked bicycle lane going the opposite way on a one way street. It’s a fantastic solution to the plethora of one way streets that dominate the old inner city neighbourhoods of Toronto – streets that are organised in a deliberately directionally discontinuous manner to prevent traffic short-cutting through residential streets since most of the inner city was built on a relatively regular grid. Unfortunately, this organisation of one-way streets makes life difficult for bicycles trying to obey the traffic laws – so let’s face it, most of us frequently cheat and go the wrong way down one way streets. And of course we always stop at stop signs too, right?

Now call me a shit-disturber, but I can’t help think that instead of making “a bicycle expressway along Bloor/Danforth” (um, what did we build that subway line for?), we should improve the ability of cyclists to legally penetrate the city’s network of one way streets through schemes such as this one. There’s even a special traffic light at Bloor at the north end of Montrose with a bicycle-only green light.

Despite commuting to work every day by bicycle, I have to say I’m not a fan of normal bike lanes – these ones improving access to the city being an exception. The reason I feel this way is that bike lanes foster the impression that cars and bicycles can’t really share the roads – that bicycles in fact need their own lanes. Sure, that means they’re sharing the asphalt – but I worry that it means in the long run that drivers won’t be used to sharing their every day roads with cyclists. In european cities where bicyclists are supported with vast networks of bicycle lanes, this is almost my impression – that once you accept that bikes need their own space, you can’t stop – all of a sudden every new road needs a bike lane, every major road – in fact european bike lanes are frequently off the road entirely which is not exactly sharing the road, is it? It’s avoiding it.

The flip side to that concern is that bike lanes prevent cyclists themselves from acclimatising to sharing the road with other traffic – leading to a sense of confidence which, while theoretically desirable, is not based in the safety reality of urban cycling. Apart from the joys I find in weaving between traffic and demanding my own space on the road without an official line to decide the matter, it concerns me that too many bike lanes make it too easy for people who are not ready for city cycling to believe that it’s safe for them to cycle.

The first car you find “standing” in a bicycle lane, forcing you out into a traffic lane you’re not supposed to be in, might get you concerned. Then as you look back to talk to your friend who’s following you in your “safe” bike lane, someone in front gets out of their parked car without looking, stepping right into the lane and forcing you to either slam your brakes on, or again swing out into traffic to avoid them – that is if they didn’t hit you with their door in the first place. Further along, you come up behind a bus which, every time it comes to a bus stop, swings over into the bike lane, forcing you to either trail along behind it (breathing it’s lovely diesel fumes – a bus stopping at every stop moves along at just the right speed to keep in front of a cyclist – if you try to pass it, usually it passes you and cuts you off at the next stop) or swing back out into a traffic lane.

These are things that happen to me every time I use a bicycle lane. These are the realities of urban cycling. But in all of those cases, the bicycle lane is actually exasperating the problem – making the violation more of an affront than it otherwise would be because the cyclist believes that they have a “right” to that lane. While that may be the “right” thing, to me that kind of attitude leads to less safe cycling – rights don’t mean anything at the moment of contact between a 1 or 2 ton vehicle and a poor little cyclist. And you can always rely on other traffic to constantly violate the “safety” of bike lanes. Urban cycling is dangerous. Will more bike lanes along all of the busiest streets in the city make this better? I doubt it. Why are we encouraging cyclists to use the busiest streets in the city in the first place?

Instead let’s make it easier for cyclists to legally move through the quiet residential streets of the city – creating their own shortcuts to every destination imaginable. Bike lanes should be reserved for the most dangerous and problematic sections of road. And for those who don’t want to cycle without bike lanes? That’s what transit is for. Whether it’s about getting bike racks on buses and streetcars, or accepting that transit really is the better way, and despite using a bicycle pretty much every day (yes, all winter too), I increasingly feel that cycling as a means of transportation in the city (rather than as a form of recreation) is not, and will never be, for everyone.

Shaw & Yarmouth – a second shot

So here’s another photo of the little heightening project at Shaw & Yarmouth shown from the side in the last post (Development in Toronto Part IV – Heightening). I don’t know if it’s a much better photo, but you can more clearly see the extra storey in comparison to the left-hand part of the building.

For those familiar with Shaw Street, you’ll recognize this little gem just further south on the same block. Nothing like a little variety added to the nondescript streetscape!

Development in Toronto Part IV – Heightening

Urban Designers have been waiting for it for ages – and it’s finally here. Heightening. The continuing strength of Toronto’s main streets fuelled by a slowly crawling gentrification has led owners in some districts to realise the potential of their buildings themselves instead of selling out and moving on. The consequence is less main street blockbusting with 10 and 20 story condo monsters with underground parking and more renovations of main street buildings – part of which is heightening, adding a floor or two to your existing building.

Now if only the same attitude would become more pervasive amongst the reams of single family homes that make up the majority of Toronto’s neighbourhoods. Perhaps then we would see more liveable and comfortable apartment units instead of the endless stream of awkwardly renovated houses uncomfortably filling the gap between high rise condo and unattainable single family house.

The current heightening hotspot is College Street west of Ossington, which I believe is a largely Portuguese community but is definitely an emerging hotspot of activity, though less centred around the arts as Queen West West.

The Curious Incident of the Disappearing Crips Tag

A couple of weeks ago I was walking through this railway underpass on Symington Avenue in Toronto’s west end, north of Dupont Street, when I happened to notice a blue spray-painted word on the concrete retaining wall at the side of the road. The word was “CRIPS”. Now I’m no expert on gang tags, but I do know there are Crips affiliate gangs in Toronto, and I know that their traditional colour is in fact blue. Given the concern in the city of late over a dramatic increase in gun violence, it’s not the most reassuring thing in the world to find a possible declaration of gang territory so close to home (read just around the corner).

The curious part is that the tag had appeared to have disappeared. I went through the underpass several times on my bicycle since first noticing the word and couldn’t find it again. I only rediscovered it about the third time I had walked through the underpass. The reason appeared to be that the blue paint was a little faded (whether because of an attempt to remove it or weathering, I don’t know), and that the difference in lighting underneath the underpass and the slowness of the eye to adapt had rendered it almost invisible to anyone not walking through the underpass on its opposite side.

I honestly don’t know what to think. I would like to tell myself that it’s just some wannabe kids acting up and playing cool. But I’m not sure if that reflects the reality of the gang situation in Toronto. At any rate, the initial almost irrational reaction of fear is I believe unjustified.

I can only think of poor old Tookie (Stanley Williams), co-founder of the original Crips gang in L.A. Tookie was executed by lethal injection in December after being in prison since 1979. Starting in the 1990’s Tookie became one of America’s best known crusaders against gangs and gang-culture, writing many well-respected children’s books on the subject and brokering a peace agreement called the Tookie Protocol for Peace. Sources indicate he was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize five times and once for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Unfortunately for Tookie and the rest of us, the first part of his life may have had the more lasting effect on the world, and kids are still being drawn in to the web of violence and the gang life. And we are all the lesser for it. Perhaps one day soon I’ll once again walk up Symington and see nothing more than a benign railway underpass, having managed to keep my faith in this city.

Three things Toronto can stop worrying about

John Barber had an amusing article in the Toronto section of the Globe and Mail today under the title “Dear worry warts: Stop fretting about our city” (see here, but it’s available online by subscription only) – for your pleasure here are excerpted from the article three things Toronto can stop worrying about that relate to urban planning and design:

“Urban living seems to promote a special susceptibility to profitless anxiety. So here are a few things not to worry about, no matter what they say.

“Parking. There is never enough of it and there never will be. But this is not a problem. Problems are things susceptible to solutions. Nobody complains about the ‘bread problem’ because bread isn’t free and some robbers charge $5 a loaf – parking is just another thing you have to pay for, subject to the usual laws of supply and demand. Not having enough of it is an existential urban condition. Ergo parking policy is pointless….

“Gridlock. No such thing has ever occurred in Toronto, a city in which travel of all kinds is still remarkably easy. With apologies to those commuters forced by bad luck, inadequate income or circumstance to travel expressways during rush hours – most commuters make the choice of where to live – there’s really not much to complain about. Indeed, there would be no traffic ‘problem’ at all if local expressways were priced like parking. Occasionally clogged but always free, they’re a bargain. GO Transit is also ludicrously cheap. And the TTC, the most businesslike of local transportation services, is extensive and brutally efficient. The only thing worse than chronic congestion is its absence, a condition known as ‘recession’.

“Advertising. I will never understand why it is considered wrong to stuff as much advertising as possible into the transit system. The ads are the most interesting things you can look at openly on the subway. You can’t see the ceilings of most Japanese subway cars for all the fluttering paper promoting racy tabloids. Streetcar ‘wraps’ are fantastic. The only thing wrong with the new televisions on subway platforms is that the screens are too small.”

I agree heartily with all three with the proviso that as I mentioned in an earlier post (A Little Request of the TTC) the television screens on subway platforms should display the time until the next train, and that I’m not sure if I would classify GO Transit as “ludicrously cheap” since it suffers terribly from having no reasonable integrated regional fare scheme.

Gridlock may in fact be an increasing issue in the 905 but whether or not it truly is a problem is an interesting question, since roads in the 905 will never be able to have the capacity to support the level of car dependency of the 905 in the long term. In that case, gridlock serves the purpose of driving home the point that transit is the only complete solution to mobility in a relatively dense urban area.

Certainly instead of spending so much time worrying about advertising on transit, we should be focussing all our energy towards making the best, most integrated transit system we can, amending the fare subsidy structure, procuring lasting and adequate commitments to transit funding and infrastructure improvements, improving routes and service levels, and experimenting with ways to address the real problems of providing transit in disparate, separated, car dependent suburban areas.

Faced with these concerns, you have to wonder what kind of people think too much advertising classifies as a transit problem in Toronto.

(with apologies to Matt Blackett, the TPSC, and Spacing – I keep picking on them and feel bad about it – they’re not such bad people, and I think Matt left a quite nice comment down on my A Little Request of the TTC post, so really I owe him one – we are all really interested in making the city a better place, we just don’t always agree on what’s wrong and how to fix it)

Beautiful Urban Moments – Part I

This might not seem like an urban moment – but since it’s but a few minutes walk from Bloor and Yonge in Toronto, it gives you an idea of the wealth that the ravines give this city. This is the Bloor-Danforth subway line as it crosses the Rosedale Ravine viewed from Bloor Street East. The Rosedale Valley Road can just be seen in the bottom of the photograph. Why we always put a road down the middle of a beautiful valley I don’t know, but it does make for one of the most beautiful roads in the city – it just happens to be mostly used as a shortcut to the Don Valley Parkway for vehicles and bicycles. Curiously enough, in almost every other direction you would see a variety of apartment buildings poking out of the foliage, but in this case we’re looking towards Rosedale itself, one of Canada’s most exclusive residential neighbourhoods.

Development in Toronto Part III – Inglis Lands

I’ve seen this project variously named King Liberty, East Liberty Village and Inglis Lands. It is “a 45-acre brownfield site located in the King Street West / Strachan Avenue area, immediately west of downtown Toronto.” The Inglis plant had been on this site off Strachan Avenue since 1881, employing at its peak 17,800 people during the second world war. The company started out building equipment for grist and flour mills, then marine steam engines and waterworks pumping engines, guns for the war effort, then consumer products after the war, including house trailers, oil burner pumps and domestic heaters and stoves, finally adding home laundry products and other home appliances for which Inglis became well known. The closure of the Strachan Inglis plant (affecting 650 employees) was announced one month after the Canada-US Free Trade agreement came into effect in 1989, and 2 years after American giant Whirlpool took a controlling stake in the company.

“The redevelopment of this site is seen as a major opportunity to create a significant new residential neighbourhood and associated employment space providing important “live-work” opportunities. Situated in the northern portion of the Garrison Common area, immediately north of Exhibition Place, these lands will play a strategic role in achieving City of Toronto policies related to residential intensification as well as embracing various smart growth initiatives. Specifically, this mixed-use development will offer this growing community new retail, office and high-tech type users.” (from IBI Group promotional material)

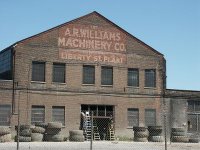

Historic buildings that will remain are in Block 12 (the central park) and Block 8. Both have connections to the old Central Prison for Men which was on this site from 1873 to 1915. The building in the park (Block 12) contains the Chapel of the Prison, is historically listed, and will be preserved as part of the park – though that probably means having a Starbucks put in. The building on Block 8 is the Liberty Storage Warehouse also known as the A. R. Williams Machinery Building at 130 East Liberty Street. This building contains part of the paint shop of the prison dating from circa 1879 – however, despite being historically listed,

Historic buildings that will remain are in Block 12 (the central park) and Block 8. Both have connections to the old Central Prison for Men which was on this site from 1873 to 1915. The building in the park (Block 12) contains the Chapel of the Prison, is historically listed, and will be preserved as part of the park – though that probably means having a Starbucks put in. The building on Block 8 is the Liberty Storage Warehouse also known as the A. R. Williams Machinery Building at 130 East Liberty Street. This building contains part of the paint shop of the prison dating from circa 1879 – however, despite being historically listed,  with many of the features of the warehouse itself (which was completed in 1929) appearing in the listing, only the southern 28m of the building will be “saved” with a 52m tower allowed to occupy the rest of the building’s footprint. The northern portion of the site was a small railway freight yard (which can be seen in the top left of the 1935 aerial photo above – north is to the left with the Exhibition Place buildings to the extreme right). The photo below is from Strachan looking west with the Inglis Plant on the left, the freight yard beyond and the Massey-Harris complex to the right. Pretty much everything in this photo is gone today except for the main railway lines.

with many of the features of the warehouse itself (which was completed in 1929) appearing in the listing, only the southern 28m of the building will be “saved” with a 52m tower allowed to occupy the rest of the building’s footprint. The northern portion of the site was a small railway freight yard (which can be seen in the top left of the 1935 aerial photo above – north is to the left with the Exhibition Place buildings to the extreme right). The photo below is from Strachan looking west with the Inglis Plant on the left, the freight yard beyond and the Massey-Harris complex to the right. Pretty much everything in this photo is gone today except for the main railway lines.

Phase 1 was the stacked townhouse development on Block 1 (that can be seen in the 2005 airphoto above) and which is now completed. These stacked towns are basically masquerading as live-work units – but whether any effort has been made to make them flexible enough to truly be live-work is questionable. I personally don’t believe this building type was appropriate; their tight ranking in rows along narrow private (sometimes pedestrian) “streets” does a poor job at promoting a good mixed-use urban image in the area and in really framing the street the way a mixed use apartment building can. To top it off, stacked townhouses in Toronto are just plain ugly most of the time – trying to look like a house but at the density of an apartment building. The marketing behind them is relatively straight-forward though – in Toronto, units with their own ground-level entrances will sell no matter where they are. Note how not a single front facade faces the small park/square on Block 1. This is not quality urban design – despite winning a Canadian Urban Institute “Brownie” award in 2005.

Phase 2 is currently under construction on Block 3 under the name “Liberty Towers” – a 24 storey building with 276 units – it’s a little unclear what else might be on that block though, so my figure of 325 units may or may not be more accurate.

Despite having a 35m height limit, Block 4 was immediately developed as a big-box Dominion supermarket with a large parking lot and a small strip mall – all one-storey. I’d classify that as embarrassing given the location, but I believe the zoning at that end precluded any residential units being built on Block 4.

We’ll see how this one pans out – there’s a chance that once the really dense buildings get in there, they’ll have found a way to save this thing. I’m worried about it though – especially from the perspective of connecivity. Directly to the north on the Massey-Harris lands there was a mixture of ugliness, misdirectedness, and beautiful moments – so lets hope some of these future phases save this area’s ass and that they do a good job on the central park and the rest of the buildings.

This image from IBI Group seems highly optimistic to me and possibly quite deceptive – I can only assume this is meant to be Block 7 looking east, but this building is now allowed to have a c. 4 storey (13m) podium and a c. 20 storey (61m) tower and will very doubtfully be such a “flatiron” signature building (it no longer appears to be so far forward on the block to create the wedge shape). The entire area is still very isolated, especially now that the Front Street Extension appears to be on hold yet again – and I haven’t found anything indicating concrete plans to improve this isolation. I also don’t think that there is enough real urban fabric here to make it a place that could stand on its own.