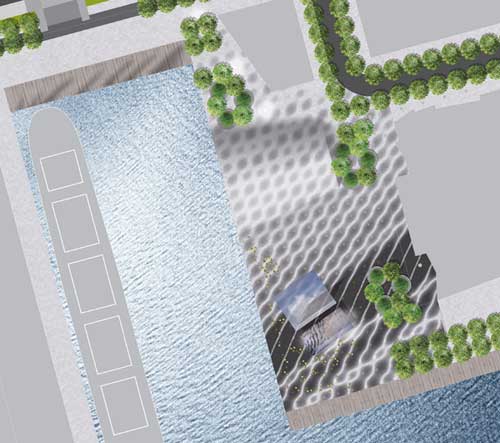

The Star’s Christopher Hume today wrote a scathing attack on Waterfront Toronto’s jury of “insiders” for its choice of Sugar Beach as winner of the Jarvis Slip Public Space Innovative Design Competition (see images from the 3 designs in our previous post).

Hume suggests that we were in fact making a choice between a couple of giant movable arms and a giant screen wind scuplture, but has the gall to say that architect Siamak Hariri may create admirable buildings but “has never shown any special understanding of the landscape”. Sorry Mr. Hume, reducing a landscape architectural public space project in a waterfront location to a choice between two sculptures (however animate) doesn’t show much special understanding of the landscape on your part either. The two features of the design proposals that seemed to attract the most attention both existed essentially in a vacuum disconnected from the site or its context, having no sensible relationship to the surrounding landscape, nor any spatial qualities that would add to the spatial experience of Jarvis Slip.

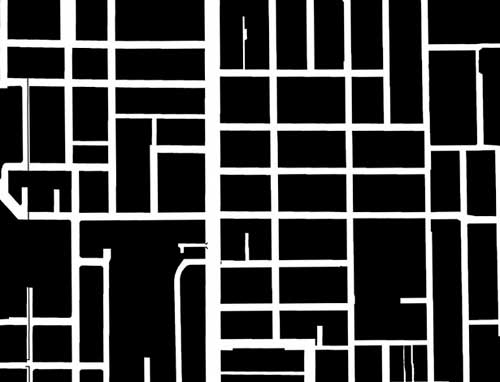

Yes, the wind sculpture by Ned Kahn would be fantastic, but what is the compelling reason for it to be in this location, and how is it remotely site-specific if it’s essentially similar to all of Kahn’s other wind sculptures? In fact, the Weatherfront team went out of its way to fuss about how we get our weather from Pearson International instead of the waterfront, but since weather stations are traditionally located at airports, the best place for this Ned Kahn sculpture would in fact be directly across from the island airport, not at Jarvis Slip. Not to mention the perversity of placing a screen of this kind across the line-of-sight of the best view from Jarvis Slip (across to the islands), or the fact that the ripples, waves and motion of water in a bay as large as Toronto’s harbour is nearly as endlessly interesting, fluid and dynamic as Kahn’s sculpture would have been, so again, why here? In fact, such a sculpture would be awesome covering one of the buildings facing Dundas Square, not here where the natural glories of Toronto’s harbour are on full display for all to see.

Hume does have a point in his skewering of the machinations of the jury in choosing Sugar Beach while proposing 14 modifications to the design including creating the beach somewhere else instead.

If you set up an “Innovative Design Competition” and then choose what was perhaps the least innovative of the entries, there is something to answer for, but in this case, maybe we should question the use of a competition such as this for this site, and the criteria for innovation we were really after – that is, innovation in public space, not in public art. The innovations in the West8/DTAH and Weatherfront designs were both essentially sculptural, while the overall designs for both were uninspiring and even adversarial to their context.

I am reprinting below the defense of Sugar Beach I posted as a comment over at Spacing Toronto:

———————–

I agree with the choice of Sugar Beach for several reasons (to the chagrin of friends at DTAH who think I have a conflict of interest, though I had nothing to do with the design). I think it’s true that it may take some selling for the idea of a beach in this location to be given credibility, but personally I think the juxtaposition of industrial and recreation uses could be exciting and interesting.

As to the year-round use, it hardly feels like the site would be a place for people to naturally convene in winter anyways – how much effort should be expended on attracting people in winter to exposed west-facing sites bound to be windswept and cold? The location of the site next to the potentially inanimate private use of the Corus building hardly bills it as the Dundas Square of the waterfront.

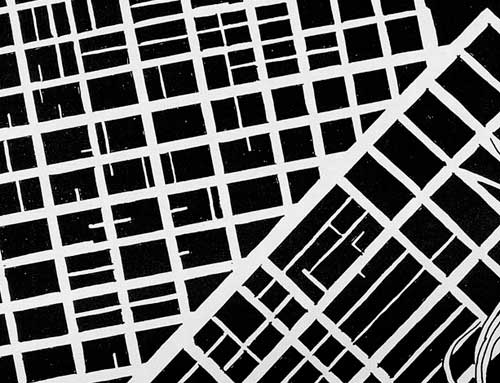

I think if you only ask 3 teams for submissions (all of whom have already done work along the waterfront) you’re really handicapping the possibilities of the location – in this case, as exciting and attention-grabbing as the West8/DTAH scheme was, it failed to really evoke or respond to the specific place of Jarvis Slip and, without the gimmick of the arms, didn’t have a leg to stand on…

I think there’s a little bit of genius simply to the name “Sugar Beach” – I can imagine years from now, with the Redpath plant long gone, the subtle evocation of the relationship carrying on in the identity of this place – “meet me at Sugar Beach” sounds so much better than “meet me at those big arms that stopped working years ago down by the waterfront”. While the name HtO was clever but gimmicky. I feel it will eventually fade as a name through lack of use, Sugar Beach as a name seems like it will have lasting power and be able to become part of the physical and psychological landscape of the city.

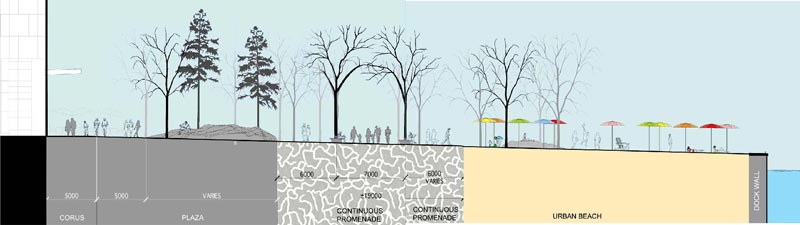

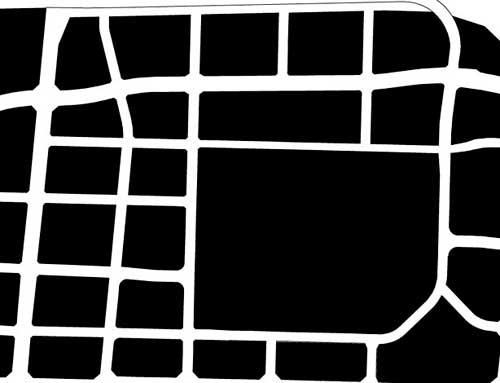

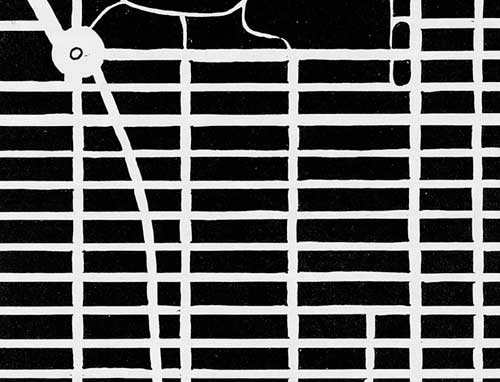

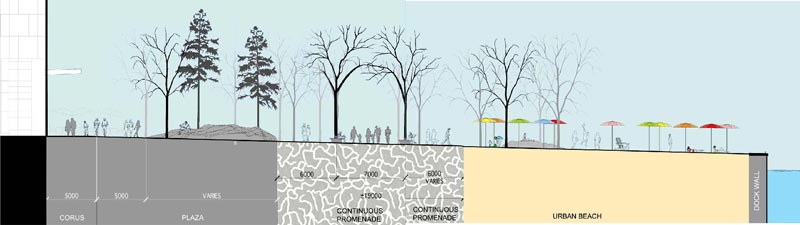

Beyond the name, the design for the Sugar Beach scheme itself was well-thought out – not too complicated or cluttered, and just seemed to be a natural extension of the city and waterfront. In particular, the use of the angled waterfront promenade continuing the line of sight from Jarvis from the original East Bayfront Precinct Plan seems highly appropriate in guiding most pedestrian/active through-traffic in a direct desire-line to continue along the east bayfront, while the more passive use of the beach wedges in on the water side of the promenade.

While some people seemed against the use of rock-mounds (maybe it depends on whether or not you like the Cumberland Park version…) I think the way that they’ve been used in the Sugar Beach scheme is appropriate and a more subtle evocation of the canadian landscape than the West8/DTAH version which seemed to be trying too hard to be canadian. The rocks coming out of the sand of the beach seems like a great idea too, while larger rocks in front of the face of the Corus building seems like a good response to the future private nature of that building.

I think Sugar Beach will be a great place, appropriate to where it is, and with the potential to be an interesting hiatus on a walk along the waterfront. I think it’s worth remembering that too much glam and style in landscape architecture rarely tends to be long-lasting, but is too easily convincing in renderings and models. Old parks maintain their charm because they’re timeless, not because they were gimmicky. While certain key, central locations can more than withstand a glam and style design, Jarvis Slip is not this location, because people have no reason to be here – given that reality, Sugar Beach wins out…

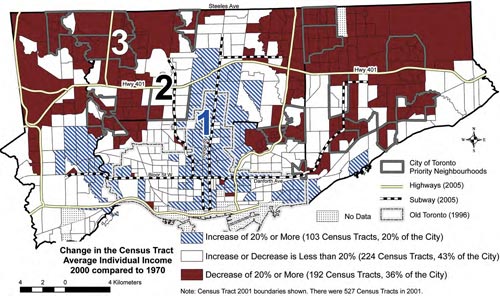

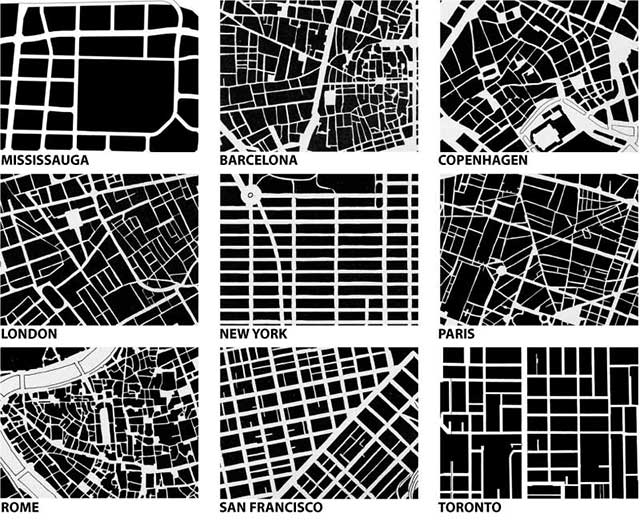

I think in the end, Sugar Beach can be said to be representing the establishment and extension of something of a “style” for Toronto’s waterfront, a style that seems built on something that has come out of this city (regardless of Cormier being from Montreal). Something in the essence of Toronto got expressed in the success of HtO – but some people seem hell-bent to turn Toronto into something “else” – no doubt they also think the ROM and AGO renovations actually have something to do with Toronto instead of just happen to be here. It seems like the ultimate test of whether you love Toronto, as it is, with its quirks, foibles, frustrations, and just want it to get better, or whether deep down, you just want Toronto to be somewhere else – Chicago perhaps, or New York, Vancouver, Montreal, London – it’s always somewhere else that’s stylish, that’s good, that has taste, that has innovation – the grass is always greener somewhere else.

But from my point of view, Sugar Beach will only add to the greenness of the grass in our garden down by the waterfront. We should stop pissing all over Waterfront Toronto – the establishment of the urban design review process implies that the members of the panel are knowingly guiding development and public space towards the greater goals in the public interest that have been established by Waterfront Toronto’s planning work – even when that means they have to override the whims of individual designers (and, god forbid, newspaper columnists). In this case, the only true test will be in what gets built, and how well it works. Until then, we need to have a little faith. All is not lost. Sugar Beach will be a great place.